KRONO ATE HIS CHILDREN

WITH: Paul Blenheim, Olga Makeeva, Dion Mills, Emily Tomlins, Tim Wotherspoon

DIRECTOR: Marcel Dorney

PRODUCER: Bek Berger (Berger With the Lot Productions)

POETURG: Eddy Burger

WRITTEN BY: Nana Biluš Abaffy

Currently in development.

WITH: Paul Blenheim, Olga Makeeva, Dion Mills, Emily Tomlins, Tim Wotherspoon

DIRECTOR: Marcel Dorney

PRODUCER: Bek Berger (Berger With the Lot Productions)

POETURG: Eddy Burger

WRITTEN BY: Nana Biluš Abaffy

Currently in development.

This project has been supported by the City of Port Phillip through the Cultural Development Fund

|

|

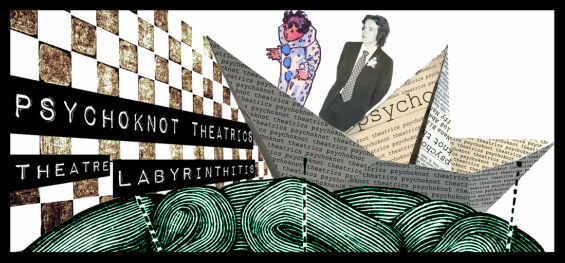

psychoknot theatrics vs royal central Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, June 2013. CONTORTED REGRESSION TO A PRIMAL TRAGIC MOMENT IN AESCHYLUS Krono Ate His Children is a tragi-comic play about love and insanity. It deals with an unstable girl called Ifh who desperately tries to connect with her emotionally abusive father Krono. Both father and daughter have selectively erased and confounded the details of their painful past and traumatic separation. No one knows exactly what has happened but all have come to a firm agreement that their lives have been swallowed by the insurmountable tragedy. Krono Ate His Children taps into the tenacious afterlife of ancient drama in an unusual way. The father and daughter’s absurd attempts at communication are realised by conflating their broken identities with those of Agamemnon and Iphigenia. Ifh loosely identifies as the sacrificed tragic heroine Iphigenia, just as Krono is identified as the child-sacrificing king Agamemnon. Through the tragic parable the father and daughter find common ground on which they are able to momentarily exist together. The cataclysmic moment of the sacrifice itself is the recurring post-traumatic nightmare which haunts the characters and stagnates their ability to move on with their lives. Through an exploration of the painful games of memory, Krono Ate His Children investigates the difficult reality of trauma and its caustic repercussions. The characters are obsessed with and defined by their personal catastrophes and suffering. Ifh proudly claims, “I am suffering personified!” The other characters in the play are Rip, Queen and Slave. Rip is the malignant best friend of Krono. The two are long time cronies who have barricaded themselves within their own impenetrable reality. Like Krono, Rip is a slightly senile alcoholic who prides himself on being a sensitive and refined aesthetician. Ifh and Rip hate one another, because Ifh sees Rip as another brick in the wall which separates her from Krono. Queen (Clytaemnestra) exists separately from all the other characters. Like the mythical Niobe, she sits silently on her throne grieving for her child. She is the fierce mother of Ifh who speaks only through poetry. Ifh adores Queen and is even sexually excited by her violence and the recollections of her slaughter of Agamemnon. Queen is the symbol of the chaotic erotic impulse that the play frequently delves into. Slave is in love with the suicidal and narcissistic Ifh and wants to save her life. He lives inside her chair/podium. He is obedient and tolerant of her abuse towards him but eventually succeeds in teaching her to be kinder. Slave believes in Ifh and would follow her to the ends of the earth. Krono Ate His Children is ultimately a play about learning how to love the world and “the bodies moving inside and through the world.” The play considers the delicate nature of family bonds and the role they play in the formation and maintenance of stable identity and mental wellbeing. It deals with the fragility of sanity, and stresses the importance of love in overcoming tragedy and explicitly rejecting suicide. It is interested in beauty regardless of unbeauty. Below its sometimes vulgar surface it is a tender play that just wants to “live a little longer.” psychoknot theatrics vs oxford Oxford University, June 2012. POWER IN PRACTICE: CLASSICAL PERFORMANCE RECEPTION WHY ARE WE HERE? Is it inappropriate to ask why we are here? Why we are devoting our lives to ancient ghosts? I was a little hesitant to admit that I was coming here, to Oxford, to talk about the Classics, about dead, white, male imperialists, about a distant and more golden age that the 1% in particular can’t seem to get over, instead of talking about the future, instead of focusing on the new, on art that is living and breathing. Is it somehow ridiculous that we are here now? Helping to further solidify the shadows cast by past giants? Is this an anti-revolutionary effort we are engaging in? A conservative movement holding us back from even attempting to nurture some small fragment of our own potential for greatness, or from looking for it in the work of our contemporaries. Ancient giants have attained so much power over the centuries that the mere mention of any one of their legendary names is enough to send shivers of awe and respect down the spines of well-bred children and staunch euro-centrics the world over. I too used to be wide-eyed and eager to obediently begin receiving instruction from the fore-fathers of civilization, and so, when in my first year of university I heard a fellow student of Philosophy 1.0.1 declare that “Plato’s just a dickhead,” I nearly collapsed. However, after listening to that student’s cogent exposition of his shocking thesis I started to realize just how liberating sacrilege can be. Nobody was above criticism any more; no Plato, no Aristotle, no Euripides - nobody. The unbearably prestigious inherited canon was suddenly no longer daunting. Back on this old continent, however, it is a different story altogether. Why such a dogmatic acceptance of the status that the classics enjoy? Most obviously, it has to be the surest ticket to respectability, the official stamp of high culture. The whole department, in fact, smacks of an elitism that my Australianisation has taught me to find repulsive. This is precisely why I always stutter when I have to tell people who my favourite writer is (Aeschylus), and what I’ve been doing for the past several years with both my theoretical and my creative work (Aeschylus again), and just general questions like, what’s your idea of fun; “yes, it’s Aeschylus, but wait, let me explain!” It is too late though. They have already sized me up, they are bored with where the conversation has gone, and, if they are kind, the look of pity appears on their face – in terms of the avant-garde, I’m as backward to them as backward can get. What they never let me explain is that my high esteem of Aeschylus is not just a cliché, it was for me not just a submissive reception of some pedigree dogma food which I was fed with a silver spoon. I love Aeschylus. His name comes up every day. For years now all the more important discussions I have been a part of have ultimately led, in one way or another, straight to him. Look closely and you might discover that he has given us, among so many other things (and the following is a random list of a few of these things, which I have discussed elsewhere): a psychological blueprint for a functional direct democracy; a possible cure for schizophrenia; the way to co-existential stability and tolerance of extreme ideological diversity; the meaning of ethics; and, the politics of ethics in practice; the meaning of ‘meaning’; and, the meaning of humanity. Now, before I hear any scoffs, I’d like to re-declare at this point that loving Aeschylus is beyond mere cliché, despite the unfortunate or just plain unfashionable associations some of the aforementioned questions may have accumulated over the millennia. It is my belief that Aeschylus’ contribution to the good of the human race is worth mentioning every once in a while. When entered into in this manner, the love of the classics regains at least part of its long-lost innocence. It becomes more sincere because it is personalized. Rather than it simply being a matter of loving some abstract notion of ‘The Classics’ because they are ‘Classical’, it is loving them for a reason. Thus, in attacking the illustrious status that the classics so effortlessly maintain, I do not deny that they may indeed deserve to have that status; I am arguing, rather, that one should be able to prove why they deserve it, or at least be open to discussing their worth, as it stands on its own, independent of any inherited privilege. WHY THE CLASSICS? ORIGIN. HERITAGE. Why the classics? This is a pretty ‘classical’ question, and I’ve heard many different answers to it, and, I don’t know about the rest of my generation, but nothing really seems to sit that well with me. Firstly, I cannot ignore the reality of the present moment. And, at the moment, what immediately strikes me as being an undeniable shaper of our reality is information – enormous amounts of technologically disseminated information. Information has always been there, safely stored away on alphabetised library bookshelves, but now it is faster, more efficient, more irresistible, and we are in the midst of it all, habitually slipping into the free falling rabbit holes of the internet, compulsively following never ending links, digesting everything and then clicking through to more of whatever waits in store on the next page. We devour a hundred different dissertations at once, and must keep reading until they have all gone away, because they are all relevant to what we are doing, we cannot let them escape, we must keep going, keep absorbing this gigantic, time consuming brew of extremely accessible multiple voices, opinions and ideas, and we cannot look away until they have all been demolished, until we have cleared them all away. Information addiction is a common 21st century problem and it seems to be getting progressively worse. Wait! Wait! You finally hear yourself yelling out. Before I drown here, I need to get to the bottom of this! Think rationally. Where did all this information begin? I want to start at the very beginning, and hold this beginning in my arms for a while until I can comprehend it. Out of this informational chaos I will carve out a path, into the past, beginning with the beginning. Why the classics? Because we locate here what we imagine to be our very own creative human origin. It is the oldest thing we can get our hands on; the commencement, the most primary, fundamental building block buried underneath everything we have today. In touching this origin, we feel as though maybe we can start again, from the ground up, somehow we are free from everything that has happened in between. History collapses. Humanity, art, can begin again, clean, new. There are so many possibilities, and it is up to us to decide how the world will be arranged, and this time around, it may just be perfect. At times, it seems unbelievable that these voices come from the same world that we still inhabit, from the same humanity that we are still a part of. Studying the ancients, in this hyper-modern age, is a form of ancestor worship. And it makes complete sense that we should feel inclined to worship them – these distant relatives of ours give us a reason to feel proud to be human creators. If we can connect with them we can perhaps begin to envision ourselves as part of a creative human collective, one that bypasses the narrow-mindedness of nationalism, classism, of political and religious division; as well as the reactions against such forms of grouping, which tend to culminate either in self-seeking individualism, or, alternatively, in alienation, where one rejects an unpalatable contemporary culture and society, and becomes, so to speak, an apolitical orphan, someone the ancient Athenians would refer to as an idiōtēs. By defending the classics we indirectly, or by extension, defend our human heritage – the version we prefer to see carved through history. THEORY VS PRACTICE Countless academic lifetimes have been devoted to writing up detailed analyses of almost all imaginable aspects of the classics. Their patience and dedication are indeed admirable – without these scholars, new generations of enthusiasts would be lost. This work has to be done, or it had to be done, but the question has to be posed now of exactly what the department is doing anymore, or what a student can say anymore that goes beyond mere repetition, that contributes something new that is worthwhile. The nature of the small, humble contributions that nobody outside of the department is really interested in, along with the prospects of discovering something original and groundbreaking being so slim, sometimes makes it seem as though the most exciting thing we can hope for is a slightly more eloquent reappraisal or summary of the field in its current state, or a focus on some very minute detail that has perhaps previously been a little neglected. The classics have been theoretically over-harvested, and for those unsatisfied with the limitations of specialised pockets of closed information, the longing for virgin territory sets in. It leads to the movement away from dead information. The holy knowledge that has been stored away on dusty bookshelves demands to be relocated into something that is capable of communicating with a living audience. An engagement with what has already been said and done, a personal interest in anything from the past, requires that there be a certain amount of freedom, of unoccupied space reserved exclusively for continuously renewable possibilities. One of the things that the university represents is the security of a system; in this case, a rationally organised, stable order in the manner in which knowledge is dealt with. What I am advocating here is not at all interested in escaping a systematic approach. From this there is no escape. There always is a ‘system’ in place, whether one chooses it or not (be it that of a university system or of popular culture). What is exciting is when a system functions outside of the strict linearity of conventional academic research. This is one of the merits of practice-based research, where the creative is the theoretical. Non-linear academic enquiry pushes the limits of scholarly examination outwards, because the theoretical thrives through the creative, is infinitely more sincere and expansive, and precise, through it. The theory that is not allowed to slip into the creative as it sees fit can become oppressively restricted since it is forced to wear a mask. In a way, what I am advocating is going straight back to the old tragic coupling of Apollo and Dionysus. Clarity and possession. Learning, teaching, theorising through creating. RECEPTION IN PRACTICE: FOOTNOTES FOR PRACTITIONERS How exactly should we go about dealing with the classics as practitioners? Who do we turn to? Where should we gather our ‘footnotes’ from, and how can these chosen footnotes be incorporated into our own creative work? And more than just incorporated, how can they help create our work? It seems to me that a classical text simply cannot be removed from its own loaded reception – the two are inseparable – the text and the reception of the text. We can never be completely alone with the text in-itself, in its pure and original form, without there always being a third presence: the baggage, the disputes among translators and linguists, among archaeologists, historians, philosophers, psychoanalysts, directors, poets – all those footnotes that have been written throughout the centuries and will go on being written, in enormous quantities, while that little ancient text always stays the same – it has said what it wanted to say and it has nothing more to contribute. The rest is up to us, the lineage of enthusiasts, but we cannot be so arrogant as to ignore the plethora of information that we have been provided with, free of charge. In my own experience with Aeschylus, it has been the footnotes, almost as much as the text itself, that have brought us closer together. Throughout all these years with him, I have felt as though we’ve both been growing, together, developing all the time, changing our minds and opinions, maturing. Through all the appendixed fragments I have found of him, he is constantly unfolding in front of me. And it seems to me that it is him that is different on each occasion, more intricate, more sophisticated, like he has just told me something new for the first time, something he himself had only realized at that very moment. Footnotes are the indispensable tools that prepare the reader for the text in front of them. When reading the classics, one has to also read the footnotes. When watching a performance of a classical text, however, is the audience to have all of that information summarised in a paragraph or two in the program booklet? Is it only the experts who are entitled to a thorough understanding of what it is they are witnessing? From all the many voices that are engaged in this discussion, practitioners can be left speechless, trying to encompass and contain the countless considerations and often contradictory insights they have come across, while at the same time attempting to go beyond everything that has been said up until this point. POWER IN PRACTICE Who is in charge here? We are. We have control over the dead, we can arrange them as we see fit. The classics are so distant and there is so little of them – several plays, poems, sometimes only fragments – there’s hardly anything there. In other words, they have left themselves wide open. It has become a little too obvious that this is just as much about us as it is about them. Whether we manage to successfully disguise it or not, this is personal. The fervour of this strange activity all of us here are engaged in is no doubt fuelled by our peculiar role as active participants, investigators, re-creators, advocates, admirers, and lovers of the poets. We are actively participating; it is not just the passive receiver alone with the text – the text almost becomes just one clue among other clues, all of which must be pieced together, must be gathered from wide-ranging and diverse sources and shaped by us into something meaningful. The classics are too important to respond to pedantically, uncreatively. Theory through creativity, through practice – this is how they spoke to us, and it seems to me to be the only way we can really speak back to them. So if hierarchies there must be, let them be transfigured, and let them collapse into one another. The power does not really belong to the past and its faithful preservationists, but to the present, to the practice. |